This section tackles the history and philosophy of feminism, a movement that has led to great strides in women’s political participation and opportunities in many places, while nonetheless deeply implicated in colonial violence in others. We also provide an introduction to Islamic gender equality work, which sometimes overlaps and draws from feminism, but is distinct in crucial ways.

Activists organized a protest in front of the Egyptian Press Syndicate to protest the mass sexual assaults against women during Eid in downtown Cairo. Photo credit: Hossam el-Hamalawy, 9 November 2006. CC BY 2.0.

What we know of as feminism coalesced in 17th and 18th century Europe, expanding upon Enlightenment ideas of liberty, rationalism, and social contracts that jarringly excluded women (and many men). Indeed, colonialism during this period exported and reinforced patterns of European patriarchy. Over the years feminism came to incorporate demands beyond equal access to political rights, as women advocated for equal participation in social and economic life. Non-white, non-Western women also raised their voices, identifying ways in which dominant versions of feminism needed to change lest they replicate other systems of oppression, such as racism or orientalism.

Feminist philosophy also led to the development of scholarship grounded in new ways of understanding the world, establishing norms of subjective and embodied research that went far beyond simply attending to sex and gender as categories of study. Questioning the possibility of neutrality, these principles premise that emotional and physical experience is a form of knowledge, that each person is interdependent and in relationship, and that our identity and place in the world irrevocably colors our perception and behavior.

Around the world members of non-European communities also worked to address what they viewed as sex-based inequities. While sometimes rejecting the “feminist” label, Muslim women and men have extensively explored scripture and classical scholarship to assess the reasoning—and contemporary validity—of fiqh interpretations. This is particularly pressing as these classical interpretations are frequently solidified in state laws that afford men authority over women, give women unequal legal recourse, and curtail women’s activities to certain spheres. In a book gathering the findings of a five-year research project by Musawah, a women-led global movement for equity and justice in Muslim families, the authors note:

In many Muslim family codes, men can unilaterally repudiate their wives, take four wives, have legal claim to their wive’s obedience (translated as wives’ residence in and sometimes confinement to the matrimonial home and consent to sexual relations with husbands) and have sole guardianship over children. Women’s access to divorce is usually restricted; they often cannot have guardianship of their children; and their claim to spousal maintenance is often contingent on their ‘obedience’ to their husbands (Mir-Hosseini et al., 2015, pp. 3-4).

An internally plural group, Muslim gender equality scholars take different approaches to their work, some employing ijtihād to determine divine notions of gender roles and justice that orient scriptural interpretation and religious practice. Others review Muslim historical and contemporary realities using the tools and lenses of feminism. These approaches bring to light and propose responses to the heartfelt queries of many groups echoed in Saadia Yacoob’s essay on hierarchy and Islamic ethics: “am I too deserving of equal dignity, of equal access to spiritual refinement”?

The learning materials below will guide students through the history of feminism and its pedagogical contributions, while also taking a critical eye to the ways in which feminism has been employed to legitimize exclusion and violence. Students are recommended to take special note of learning material 4.4.2, on feminist pedagogy, as it will be referenced several times throughout the section. The module will then introduce an overview of Muslim gender equality work and its internal contestations, and provide an example of the ways in which a gender equality and feminist lens can open our eyes to additional, but no less important, ways of understanding scripture and creation.

Key Terms:

- Feminism

- Social location

- Situatedness

- Embodied

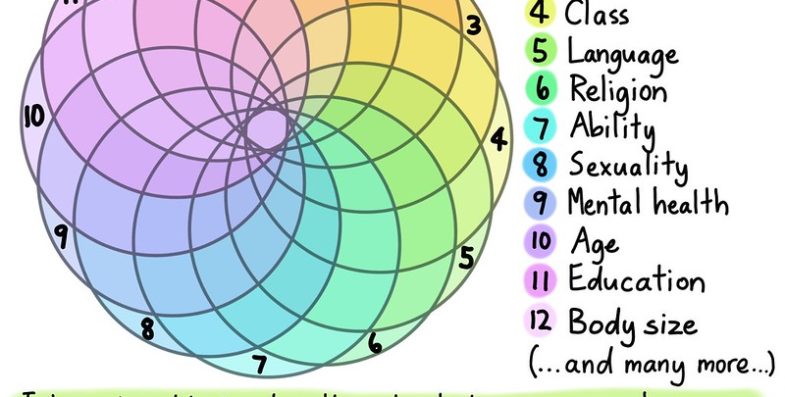

- Intersectionality

- Structures of oppression

Learning Materials:

4.4.1 The History of Feminism

How did Western feminism emerge, and what inequities did it seek to remedy? (Ikonta Bloke/"Deeds not Words")

Read More

4.4.2 A Guide to Feminist Pedagogy

Embodied and collaborative knowledge and critical attention to power structures are integral to feminist pedagogy. (Anne Rayner/"Conversation on Teaching")

Read More

4.4.3 Intersectionality

Overlapping systems of gender and racial oppression delayed Black women's vote in the US for over 45 years. (Sylvia Duckworth/ "Intersectionality")

Read More

4.4.4 Imperialist Feminism and Liberalism

Colonial feminism has helped justify military ventures that have killed hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children throughout the Middle East. (US Army/"Grape Drying House")

Read More

4.4.5 Re-Situating Intimacy, Affect, and Critique

How can feminist pedagogy shift or expand the way we understand religious texts? (Jim Boud/”Colorful Family”)

Read More

4.4.6 The Challenge of Gender Equality

Gender equality means laws that permit women to enjoy dignity, security and respect in the family and full participation in society. (UN Women/"Musawah")

Read More

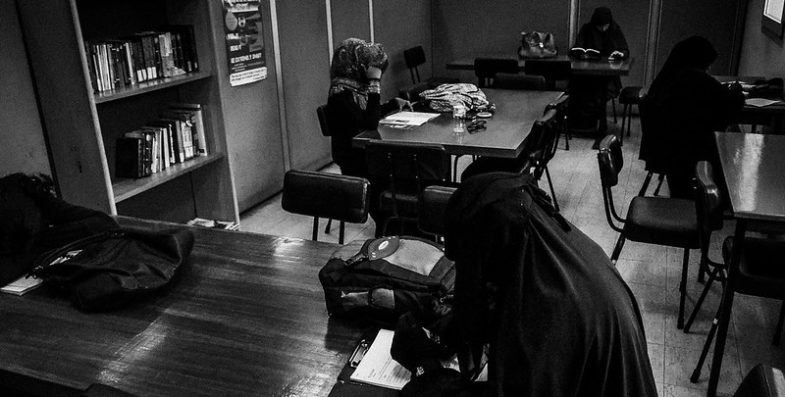

4.4.7 Claims to the Sacred

Since God is just and all-knowing, how should we confront "the possibility that the Qur'an may not be reconcilable with contemporary values of male-female equality"? (Michał Huniewicz/"Library")

Read More

4.4.8 Beyond the Text: Between Islam and Feminism

When embodied experiences of injustice come up against religious texts that produce gendered injustice, it may be necessary to move "beyond" the text. (Stefanie Eisenschenk/"Isfahan Women's Mosque")

Read More

4.4.9 The Interpretive Legacy of Qiwamah

Classical and contemporary exegetes have turned a limited instruction into a justification of pervasive male authority over women. (Jaguar MENA/"World Driving Day")

Read More