3.4.2 Avicenna and the Mind-Body Problem

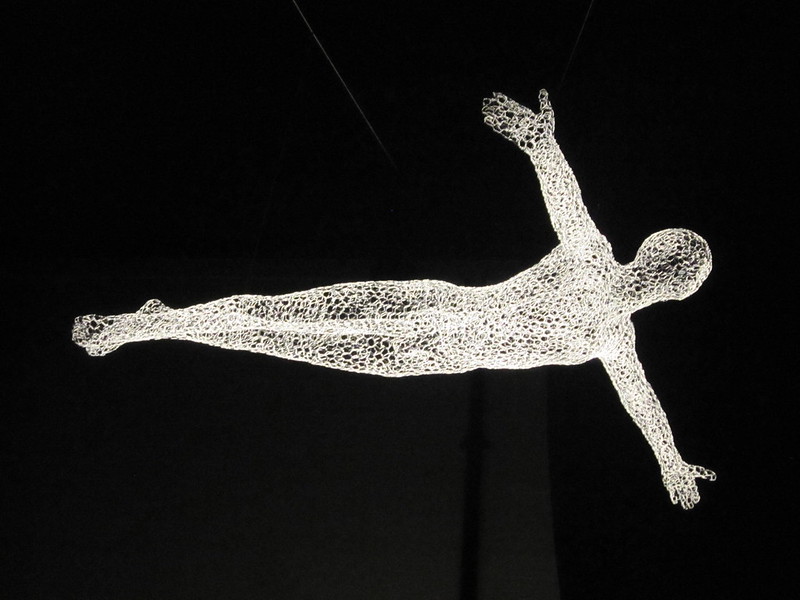

But the most famous [thought experiment] is the so-called ‘flying man’ thought experiment, devised by the most influential philosopher of the Islamic world, Avicenna (in Arabic, Ibn Sīnā, who lived from 980 to 1037 CE).

Imagine that we learn “everything” about the physical or material properties of someone’s brain (or even their whole body). Does this mean that we also know their subjective experiences too? For instance, do we also learn something about what it is like to be that person or even the content of their experience when they taste a sweet candy? Some philosophers believe that we don’t and use this as an evidence against corporeality of consciousness. This, however, raises important questions: if consciousness is not material, then is it even possible to attain scientific knowledge about consciousness? For instance, can we learn anything about consciousness by studying neuroscience? How does this incorporeal consciousness interact with our physical body? And again, is science able to tell us anything about this interaction?

Read: What Can Avicenna Teach Us About the Mind-Body Problem? // AEON

Guiding questions:

- How did Avicenna and Aristotle differ in their proposed relationship between the body and the soul? How would each answer Dr. Barseghyan’s question: “Is mind a substance?” in learning material 3.3.5?

- How does Avicenna’s argument challenge metaphysical naturalism? Remember, the only evidence this “empirical metaphysics” accepts is focused on the form and function of materials.

Thumbnail: “Flying Man,” Durham Lumière festival 2011. Photo credit: eltpics. CC BY-NC 2.0.